Powerful perspectives from Treatment Not Trauma leaders

Latesha Newson, Kennedy Bartley, Arturo Carillo, and Eric Reinhart at our summit last month

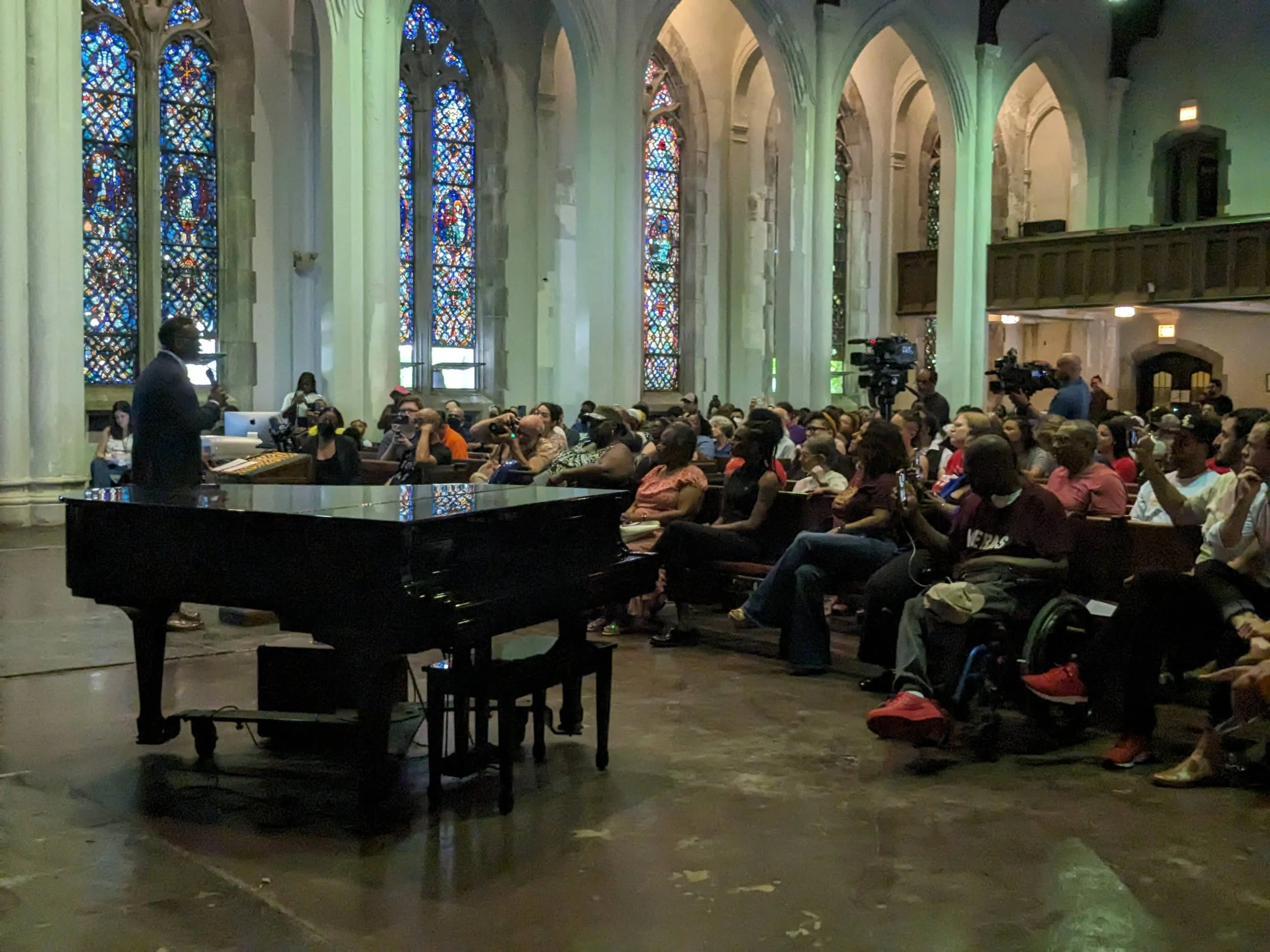

Our Treatment Not Trauma summit last month featured not only Mayor Johnson but a panel of leaders from the campaign. They shared insights valuable even for many of us who have been working on the issue for years! Read and reflect on what they said here, especially if you missed the event — or share this with someone who missed it!

Should police be part of mental-health crisis response?

Latesha Newson, President of the Illinois chapter of the National Association of Social Workers, weighed in. She drew on her experience working with some of the people most often thought of as potentially violent: at-risk youth in group homes. “When we’re looking at systems, we have to look at, ‘how do we safeguard the rights of others?’ Because when police engage in ‘de-escalation,’ it’s very much ‘you have to do what I say.’”

She went on: “I can’t unsee some of the things which I witnessed. What I witnessed, seeing a police officer slam a 17-year-old to the ground, I cannot unsee that… We’re talking about a 17-year-old who had autism. Who could not communicate… who needed help. Who needed someone to be patient.”

The City is piloting what it calls “co-responder” or “multi-disciplinary” response, where a social worker and EMT respond to mental-health 911 calls WITH a police officer. The City also has a tiny pilot of responses with just a social worker and EMT – without a police officer. The City reports that this police-free pilot has NEVER required police back-up. Said Newson about all the work she and her fellow social workers do: “The thing as a social worker that we often get asked is: Are social workers committed to this work without police? Absolutely. We do it every day.”

Why do these clinics need to be public — run by the City?

Can’t they just be funded by the City and run privately, by nonprofits?

Dr. Arturo Carrillo, Deputy Director of Health and Violence Prevention at the nonprofit Brighton Park Neighborhood Council, shared his first-hand experience. Carillo remembered working as a mental-healthcare provider at a nonprofit when the free City clinics closed under Mayor Emanuel a decade ago. “We had a lot of people fall through the cracks, who were looking for services, people we served, people we couldn’t… People died as a result of those political actions.”

Eric Reinhart, Northwestern University doctor and anthropologist, connected 1990s “welfare reform” to the push in recent years to dismantle public health infrastructure, replacing it with privatized systems.

At first glance, the private organizations (nonprofits) that the City funds to provide mental health care may seem to be cheaper, at least in terms of the City government’s budgeting. But this is because they tend to offer individuals a limited number of counseling sessions, and they often charge some sort of fee, creating a barrier to people who need care most. They also tend to be staffed by counselors who are poorly paid, not unionized, not licensed, and only recently graduated from school; when they get licensed, they tend to leave for better-paying jobs, leaving clients and patients behind (there is high turnover).

By contrast, the City’s mental-health centers offer indefinite therapy and psychiatry. They are free to all, regardless of insurance and immigration status. And they are staffed by counselors who are decently paid; unionized by the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees; and at the clinics long-term. All this amounts to infrastructure – not buildings, but solid structures for delivering the care we need.

Kennedy Bartley, the new executive director of United Working Families, added: “There’s an important part of Treatment Not Trauma that says, these [mental-health] centers must be public… the public aspect is non-negotiable. It’s important that folks understand the importance of public infrastructure, as well as the impact it has on the workforce and the people receiving the care.”

"Isn't it about time that we created an alternative for crises that do not require a police response?" -Mayor Johnson at our summit last month

We’re well into 2023. Where do we go from here?

Panelists also emphasized the historic opportunity Chicago now has to reverse decades of cuts to public clinics, and to serve as a model to other cities across the country. Bartley noted, “Now we have a mayor who has won, based on exit polling, not despite his public safety platform but because of it.” Reinhart added: “We have a unique alignment of the stars right now, with different progressive actors who are really committed to building public infrastructure. And you cannot have successful public health without public infrastructure,” like public clinics staffed by long-term counselors.

Reinhart acknowledged the steep climb still ahead to prevail against our current system of profit-driven healthcare and mass incarceration. But he reminded us that the status quo “only changes through this kind of activity – ground up organizing. People in positions of power are not incentivized to do this work.”

Looking out at all the Chicagoans gathered for the summit, he added: “It’s people in this room who do this.”